Several earlier posts have raised the question of rational life planning. What is involved in orchestrating one's goals and activities in such a way as to rationally create a good life in the fullness of time?

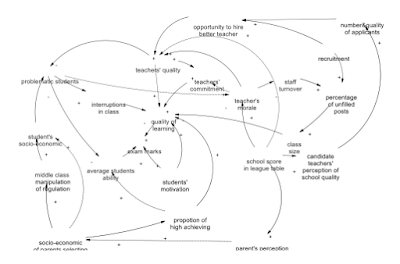

We have seen that there is something wildly unlikely about the idea of a developed, calculated life plan. Here is a different way of thinking about this question, framed about directionality and values rather than goals and outcomes. We might think of life planning in these terms:

This scheme is organized around directionality and regular course correction, rather than a blueprint for arriving at a specific destination. And it appears to be all around a more genuine understanding of what is involved in making reflective life choices. Fundamentally this conception involves having in the present a vision of the dimensions of an extended life that is specifically one's own -- a philosophy, a scheme of values, a direction-setting self understanding, and the basics needed for making near-term decisions chosen for their compatibility with the guiding life philosophy. And it incorporates the idea of continual correction and emendation of the plan, as life experience brings new values and directions into prominence.

- The actor frames a high-level life conception -- how he/she wants to live, what to achieve, what activities are most valued, what kind of person he/she wants to be. It is a work in progress.

- The actor confronts the normal developmental issues of life through limited moments in time: choice of education, choice of spouse, choice of career, strategies within the career space, involvement with family, level of involvement in civic and religious institutions, time and activities spent with friends, ... These are week-to-week and year-to-year choices, some more deliberate than others.

- The actor makes choices in the moment in a way that combines short-term and long-term considerations, reflecting the high-level conception but not dictated by it.

- The actor reviews, assesses, and updates the life conception. Some goals are reformulated; some are adjusted in terms of priority; others are abandoned.

This scheme is organized around directionality and regular course correction, rather than a blueprint for arriving at a specific destination. And it appears to be all around a more genuine understanding of what is involved in making reflective life choices. Fundamentally this conception involves having in the present a vision of the dimensions of an extended life that is specifically one's own -- a philosophy, a scheme of values, a direction-setting self understanding, and the basics needed for making near-term decisions chosen for their compatibility with the guiding life philosophy. And it incorporates the idea of continual correction and emendation of the plan, as life experience brings new values and directions into prominence.

The advantage of this conception of rational life planning is that it is not heroic in its assumptions about the scope of planning and anticipation. It is a scheme that makes sense of the situation of the person in the limited circumstances of a particular point in time. It doesn't require that the individual have a comprehensive grasp of the whole -- the many contingencies that will arise, the balancing of goods that need to be adjusted in thought over the whole of the journey, the tradeoffs that are demanded across multiple activities and outcomes, and the specifics of the destination. And yet it permits the person to travel through life by making choices that conform in important ways to the high-level conception that guides him or her. And somehow, it brings to mind the philosophy of life offered by those great philosophers of life, Montaigne and Lucretius.